Zeely Read online

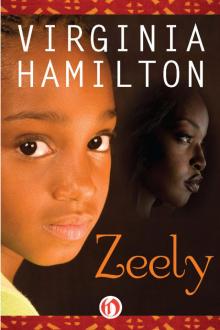

Zeely

Virginia Hamilton

Illustrated by Symeon Shimin

FOR

LEIGH HAMILTON ADOFF

AND

ETTA BELLE HAMILTON

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

A Biography of Virginia Hamilton

ZEELY

1

THERE WAS AN awful racket and swoosh as the books John Perry carried slipped out of his arms and scattered over the floor.

“Wouldn’t you know he’d do it? Wouldn’t you just know it!” The voice of his sister, Elizabeth, echoed through the huge waiting room. Her mother shushed her.

“After all,” said Mrs. Perry, “it’s not so terrible to drop an armload of books. It could happen to anyone.”

“But why does it happen to us?” Elizabeth cried. “And always when we’re in a hurry to go somewhere!”

John Perry stood close to his father. He wanted to pick up his books, but the effort of running after them and bending down where they lay was more than he could make. He could not get his legs to move. Never had he been in a train-station waiting room. It was full of quiet people quietly going places. Now all of them stared at him. He lowered his head, trying to hide his face.

“No harm done, John,” Mr. Perry said. “Next time, you needn’t carry so many books.” In a moment, he had gathered them up, giving half to Elizabeth to carry and half to John.

“No harm done!” Elizabeth whispered. “Goodness sakes, everyone in the whole place will think we’re just little babies!”

“Elizabeth, stop that whispering,” her mother said.

Elizabeth clapped her hand over her mouth. She didn’t know she had spoken out loud to herself. She hadn’t meant to. But she often talked to herself when she was nervous or upset. Like John, she’d never been in a train station. Before, her father and mother had driven them to the country. This time would be different.

“Aren’t train stations just grand?” she said. “Look at those pillars—I bet they’re all of three feet around. And the windows! Did you ever see anything so very high up?”

The windows were enormously wide and high. John Perry forgot his fear and lifted his head. He smiled up at the windows. Sunlight streaming down exposed sparkles of dust in a shaft to where they stood. Mr. and Mrs. Perry looked up, too. They all stood there, separated from the busy waiting room by the peaceful light and shadow.

It was Mrs. Perry who remembered there was a train to catch. “Oh, my! Hurry, you two!” she said to John and Elizabeth.

Elizabeth fell in step beside her father, who had started toward the train platform. Mr. Perry carried both John’s and Elizabeth’s suitcases. He urged them along more quickly, for the gate to the train had opened. Most of the people had gotten aboard.

“Elizabeth, I want you to sit and act like a lady,” said Elizabeth’s mother.

Elizabeth did not look back to where Mrs. Perry walked with John. “Goodness,” she said to herself, “do you think I don’t know what’s what? Leave me alone and I’ll do what I’m supposed to do!”

Elizabeth heard her mother talking to John. “Remember to comb your hair,” she was saying, “and don’t bother people with questions.”

“You can tell him not to open his mouth for the whole trip.”

“Elizabeth,” her father said, “calm down.”

“Just tell him not to bother me!”

“Elizabeth!” her father said.

“Mind that you do whatever Elizabeth says . . .” It was Mrs. Perry talking to John.

Elizabeth heard her. She smiled and held her head up like a proper lady.

When Elizabeth first saw the train, she stopped. Mr. Perry shifted the luggage to one hand so he could take Elizabeth by the arm and lead her along. “I’m about to drop a suitcase,” he said to her, “so you’d better hurry.”

“Is that it?” Elizabeth said. “Is that the train? How do we find our seats?” The train was quite long. Billows of steam rose from beneath the engine.

“I bet it weighs a ton!” said John, coming up behind Elizabeth. He walked around, looking at the engine. “I bet I could climb it,” he said. “I bet I could make it go fast!”

Mrs. Perry hurried them aboard. Mr. Perry found their seats for them without any trouble. He put their suitcases in a rack overhead. When John and Elizabeth were seated, Mr. Perry stood a moment, looking down at them.

“Now remember,” he said to Elizabeth, “after the midnight stop, the train will not stop again until morning. And the first stop of the morning, you and John gather your belongings and get off.”

“Where do we get off?” Elizabeth asked. “Which is front and which is back?”

“Where’s the bathroom?” asked John.

“Is there a water fountain?” asked Elizabeth.

“You can get off at either end,” Mr. Perry said. “Where you find a door open and the conductor waiting, get off.” Then, he showed them where the bathrooms and water fountain were.

Seated again in her seat, Elizabeth made her fingers dance on the window. “Do I have to tell anyone when I’m getting off?” she asked her father.

“Just get off at the first stop of the morning,” Mr. Perry repeated. “You’ll find Uncle Ross waiting for you there on the train platform.”

There was little else to say. Mrs. Perry leaned down and kissed Elizabeth and John. She told them to be good and to have a good time. They were to remember to obey Uncle Ross and not to play too hard. Mr. Perry kissed them and then looked carefully at Elizabeth.

“And now,” he said to her, “I leave it all to you.”

Elizabeth smiled at her father, tossed her head and looked as though she could take care of anything.

Mr. and Mrs. Perry hurried off the train. They had only a few seconds to wave at Elizabeth and John before the train pulled out of the station.

2

ELIZABETH FORGOT ALL about sitting like a lady. She sat on her knees with her head pressed against the window. The glass cooled her hot face and hands and she was able to put her thoughts together.

“Well, the school term’s over,” she said. Her lips moved against the window but her voice made barely a sound. “We’ll spend the whole summer on the farm with Uncle Ross. I ought to make up something special just because we’ve never ever gone alone like this!” She began figuring out what she might do that would be as important as travelling to the country without her father and mother.

John Perry leaned around Elizabeth to see out the window. He was terribly excited about making the trip but his manner was not as sure as his sister’s. He was smaller than Elizabeth, but otherwise he was enough like her to be her twin. His eyes were black, like hers, and his skin, brown, with a faint red hue. He had a shock of dark, curly hair that tumbled over his forehead just as Elizabeth’s did.

“You know what I’m going to do?” he said to Elizabeth. “I’m going to take off my shoes and socks. I don’t see why I have to wait until we get to Uncle Ross’ before I go barefoot.”

“You’d better not,” Elizabeth said. “I’ll tell mother and you’ll be sorry.”

“You’re the meanest girl I know!” John said. He sat back glumly in his seat.

Elizabeth wore short pants and a shirt for the train ride. There were seven strands of bright beads looped around her neck. She would have loved making the trip without John. She liked being by herself. Alone, she could be anybody at all and she would have only herself to take care of.

The train swept through a

long tunnel. Elizabeth sat very still. She could feel John, rigid, beside her. “Are you scared, John?” she giggled. “Don’t be afraid. It’s just a mean, black, spooky tunnel!”

John held on tightly to the armrests of his seat. “I don’t care for tunnels,” he said. He had never been in a tunnel on a train and he did not like it at all.

By the time the train entered the open air again, Elizabeth had figured out what special thing would be as important as travelling alone to the country.

“I want you to listen,” she told John. “From now on, you are to call yourself Toeboy—understand? No more John Perry, and not just for the train trip but for the whole summer.” He was Toeboy, she told him, because at the farm he could go around without shoes all the time if he wanted to.

“I’m going to be Geeder,” she said. “I am Miss Geeder Perry from this second on. Horses answer to ‘Gee,’ don’t they? I bet I can call a mare to me even better than Uncle Ross!”

Toeboy whinnied and began to prance up and down, knocking into the pile of books stacked on the seat beside him. They clattered into the aisle. It took Geeder ten minutes to quiet her brother without raising her voice or hitting him.

“I could just give you a good smack, Toeboy!” she said. She was furious but didn’t dare touch him. In the last few weeks, Toeboy had become fond of letter writing. He would whip out his note pad and scribble off something to her father if she so much as looked at him.

“Now, I’m not going to yell at you,” she said, “because then people might stare. They’ll think I’m not old enough to take care of you.”

“You’re not,” Toeboy said. “I can take care of myself, thank you.”

Geeder ignored him. She made a neat pile of the books on the floor in the space between the seats. The train rushed on as the last sunlight of the day slanted into rows of tall apartment buildings.

“Why do you get the window seat?” Toeboy asked, after a while. He was tired of leaning around Geeder to see.

“Because I’ve got it,” Geeder said, “and I’m going to keep it.”

Toeboy could tell by the tone of her voice that she meant what she said. He decided to read his books.

Geeder pressed her face against the window. She knew Toeboy was beside her and that their coach was fairly full of people. But she felt cut off from him, from the train, as if she were outside with the scenery.

“I never thought there could be so many buildings, with so many windows and people.” Geeder’s lips moved, making the slightest sound.

The train moved along an elevated track and she could see building after building for what seemed miles. The train went so fast she felt lonely for all the people left behind. Long streets looked like spokes of a wheel connected to nothing and going nowhere.

“What things happen to all these people?” Geeder whispered. “I don’t suppose they all have farms to go to in the summer, like me and Toeboy.”

That made her smile. Oh, it was nice that school was over so that she and Toeboy could leave. . . . It wasn’t that she didn’t like her home. She liked it well enough. You could go to the park or to a show. You could go for a drive in the car and have hamburgers and ice cream or you could play along the river. There was lots to do. But lately she’d grown tired doing things she had done time after time. It wasn’t that she liked going to Uncle Ross’ any better. The truth was that she didn’t remember what it was like there.

“Let’s see, there’s the farm and the town, and there’s Uncle Ross,” she said to herself. But try as she might, she couldn’t recall what she did at the farm three years ago. “Maybe I didn’t do anything. Maybe I was just too young to do much.”

This time, she promised herself, she would do everything and see everything and remember everything she saw.

“I won’t be silly, either. I won’t play silly games with silly girls.”

Suddenly, her father’s last words came back to her. At the same time, she saw that the tall buildings had given way to open country. There were houses and a few farms and fields. The train had gone beyond the river and she hadn’t seen any of it. From then on, she set her mind on seeing everything. The waning day she saw as clear as morning in the country; her father’s words, bright as sunlight in the fields.

“And now, I leave it all to you,” her father had said.

“Why, he means something will happen and I’m to take care of it!” she said.

Toeboy thought Geeder spoke to him. He’d been waiting for her to say something above a whisper so he would know she wasn’t still angry with him.

“Geeder,” he said, softly, “just look at this.”

She ignored him.

“Geeder, it’s something you’ll never believe.”

“Toeboy, you read your books and don’t bother me.”

“It says here,” he began, “there are these people living way in the middle of Australia where there isn’t any water. When they want a drink, they pick a big, fat frog and squeeze all the water out of it into their mouths.”

Geeder gasped and spun around in her seat. “That’s just awful!” she said, taking the book away from him to look it over.

“It doesn’t hurt the frogs,” Toeboy said. “They just go along until they fill up with water. Then, they get drunk up again.”

Geeder tossed him the book. “Please don’t bother me, Toeboy. I’ve too much to think about without worrying about you.”

“What do you have to think about?” he asked.

“Oh, things,” Geeder said, “things that happen.”

“What things?” he asked.

“Never you mind, Toeboy,” she said. “Be quiet and read your books.”

Toeboy reached in his pocket for his note pad. Geeder saw him. She at once smiled pleasantly at her brother.

“Pretty soon, we’ll go eat,” she said, “and you can have ice cream and cake after you have dinner. Oh, we’ll eat everything and then we’ll come back here. They’ll turn out the lights and you can sit by the window. You’ll be able to see everything in the night—won’t that be fun? Then, we’ll go to sleep and before you know it, we’ll be there and Uncle Ross will take us to the farm.”

Toeboy forgot about writing to his father. The mention of food made his mouth water.

“Will the dining car be scary?” he asked.

“Not like the tunnel,” she said. “Don’t you worry. I’ll take care of it.”

3

THE NIGHT RIDE PASSED quickly, as Geeder said it would. The trip had seemed almost too short. In the morning, Uncle Ross was there at the station to meet them. Geeder had nearly forgotten what he looked like. She had a picture of Uncle Ross in her wallet and a picture of him in her mind. The one in her mind was closer to what she saw waiting on the train platform: a big, powerful man, like her father, whose smile was broad and gentle.

Uncle Ross’ eyes shone as he caught sight of them and he tipped his hat eagerly with a friendly swoop of his arm. As Geeder ran up to him, laughing, the suitcase banging against her leg, he held out an arm for her to hold on to.

“Well, look here!” he said. “Look what’s come to stay!”

“I’m Toeboy!” Toeboy shouted, running up and catching hold of Uncle Ross’ free arm. “The train wasn’t scary at all.”

“And I’m Geeder,” said Geeder. “You must remember because we’ll be Geeder and Toeboy for the whole summer on the farm.”

“Geeder, is it?” Uncle Ross said, “and Toeboy. New names for a new summer. I like that! Give me a chance to catch my breath and I won’t forget those names, ever!”

Uncle Ross hurried them into his battered old truck. Geeder recalled that it smelled always of leather and cigars.

At the farm, Geeder saw everything for what seemed the first time. She went in and out of the rooms, looking over all the antique furniture and fixtures Uncle Ross had collected at auctions over many years.

Uncle Ross and Toeboy walked behind her. “I’d hate to think you’d forgotten what my house looked

like inside,” Uncle Ross said, teasing her.

Geeder stood fingering a faded piece of silk folded neatly on an old end table. “It’s not that I don’t remember,” she said. “I guess it never mattered before whether I remembered or not.”

“But it matters now?” Uncle Ross asked.

“Oh, yes,” Geeder said. She felt a sudden, sweet surge of joy inside. “Everything matters now!”

“Why?” asked Toeboy.

“Just never you mind,” she said to him. “But I’ll tell you this much. I’m three years older than the last time I was here. That means I know ten times as much as I did then.”

Uncle Ross smiled, noting the great change in the children. He said nothing about it, however. He left them so they could roam the house on their own. “Well, call me if you find anything you don’t know about,” he said to them as he left.

There was a pantry in Uncle Ross’ house. Toeboy and Geeder hung on to the door and looked inside carefully.

“I don’t remember this at all,” Toeboy said.

“Well, I do,” Geeder said. “I don’t remember it being so large, though, with so much food.”

They couldn’t decide if the pantry had been there the last time they visited the farm, so they called Uncle Ross. When he came, he told them the pantry had been just where they found it since the house was built.

“There’s not another house in these parts with a pantry this size,” he told them. He stood rocking on his heels in the center of the room, smiling proudly. “Each year, I put up beans, tomatoes, applesauce and jelly, among other things. Oh, I don’t use half of it in a year,” he said, “but I like giving it to folks in the village. These days, not many people put up food the way I was taught to.”

The pantry was a large square. On every side were cupboards full of canned goods up to the ceiling. Geeder walked to the center of the room and slowly turned around until she had every cupboard fixed in her mind.

“Isn’t it just the nicest place?” she said. “I love it, with all the jars and big cupboards.”

Uncle Ross laughed. “Well, then, you can come in every day and pick out all the food we’ll need for each meal. That way, you’ll get to know this pantry as well as I do and it will get to know you.”

The Planet of Junior Brown

The Planet of Junior Brown Willie Bea and the Time the Martians Landed

Willie Bea and the Time the Martians Landed Zeely

Zeely Bluish

Bluish Mystery of Drear House

Mystery of Drear House M.C. Higgins, the Great

M.C. Higgins, the Great Sweet Whispers, Brother Rush

Sweet Whispers, Brother Rush The House of Dies Drear

The House of Dies Drear Arilla Sun Down

Arilla Sun Down Cousins

Cousins